In the spring of 2013, I accepted an offer to teach English in China after a year of fruitlessly trying to find a decent job in my home country. The problem? Teaching wasn’t my profession, and I didn’t speak a word of Chinese. But I was young, eager to travel, and willing to embark on an adventure. So I made my move, braced with a phrasebook of essential Mandarin Chinese and a PDF of Jim Scrivener’s Learning Teaching.

Exploring the unfamiliar

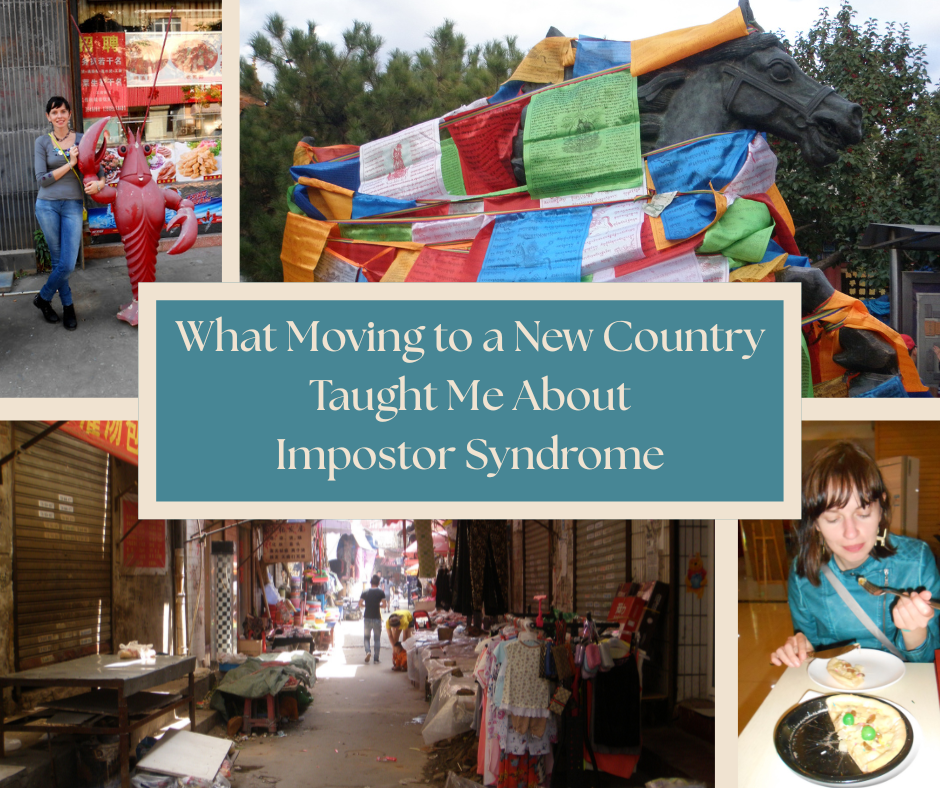

I’ll admit from the start: I didn’t know much about China besides the obvious. Landing in Shanghai and enjoying this bustling city for a few days was an easy start. I loved the brand-new skyscrapers and the Old City with its traditional architecture. However, my workplace was located in Huainan, an eight-hour train ride from Shanghai.

Life in Huainan was very much different from life in Poland. The language barrier was an obvious issue; I couldn’t speak Chinese, and most locals couldn’t speak English. But that was just the start.

Growing up in Europe, I assumed that all cities in the world have a distinct city center: either a market square or a main road with historic buildings, nice cafes, and classy restaurants. Huainan didn’t have a city center, or at least I haven’t found it in the 6+ months I spent there. The urban landscape consisted of apartment buildings, schools, hospitals, street markets, and shopping centers. It was difficult to distinguish one block from another. It was also virtually impossible to give directions, as there were no points of interest that could serve as markers.

Wherever I turned, I encountered unfamiliar things. A person burning a pile of fake money on a busy street crossing. A well-dressed lady killing a rooster on the sidewalk. My bed had a bamboo mat instead of a mattress, and the kitchen had a rice cooker but no oven. The first visit to a supermarket was like exploring an alien civilization—I couldn’t recognise 99% of the items on shelves. Where’s pasta? Where’s cottage cheese? Where’s bread?! And why are chicken feet sold as snacks?

I had so many questions and very little answers.

Can I fake it till I make it?

Starting a new job is often difficult. Starting a new job in a new city, an unfamiliar country, and a profession I didn’t know was on a whole different level of difficulty. I encountered many bumps on the road: handling miscommunication with my Chinese colleagues, managing bosses’ expectations, planning lessons without proper coursebooks or other teaching resources, and being unable to access various websites due to online censorship.

After the initial excitement of my new adventure passed, a new question appeared in my head: What was I doing here? Was coming here a mistake?

Moving to China made me realise my own ignorance about the world outside of Europe. And it wasn’t a comfortable realisation for an idealist Liberal Arts graduate who always considered herself very open-minded and culturally intelligent. I thought that the culture shock was a thing of the past and that it wouldn’t affect me, and yet it did.

Of course, I wasn’t the only person in the world experiencing this. Cultural shock among various expatriate groups has been studied for years. It’s well established that the level of difficulty experienced when adjusting to a new country can be influenced by various factors: personal traits, individual coping mechanisms, the differences between home culture and the new culture, etc.

Meeting other expats and venting about my own anxiety, frustration, homesickness, and loneliness helped me realise that many people felt the same way. We all felt that we didn’t belong there. But talking about our struggles didn’t make them go away. I faced a difficult choice: quit and go back home, or adapt to the situation.

Quitting meant returning to the 27% youth unemployment rate in Poland and struggling economically for a foreseeable future. Staying in China meant having a job with a decent salary and living in an apartment paid by my employer. So I chose the latter and braced myself for the challenge.

New country, who this?

Adjusting to living in China meant learning enough Mandarin to get by, making friends with the locals, accepting everyday customs, and learning as much as I could about the culture and history of this ancient country.

Surprisingly, making friends was the easiest part: I met many wonderful people who were eager to learn about my life in Europe and share their stories in return. They helped me pronounce Mandarin phrases, invited me to traditional holiday events, shared their favourite food, and explained the logic behind local conventions.

I made plenty of effort to gain knowledge about China from books and articles I could find online. And I noticed so many differences between my home country and my new place of living that it was fascinating. Things I took for granted weren’t so obvious anymore.

After a while, I was able to have a basic conversation at my favourite vegetable stall. I stopped seeking European products and found my favourite Chinese foods (plus, learned how to cook them!) Local holiday observances didn’t baffle me anymore, as I understood the legends they were associated with and was happy to participate in celebrations.

Of course, I didn’t fully embrace local habits and was still very much a lǎowài (= foreigner in Mandarin Chinese) but I managed to quieten down that worried voice inside of my head telling me that I was an impostor that didn’t belong. Sure, China wasn’t my country. But that didn’t mean I couldn’t enjoy my life there and learn from this experience.

Finding my way: in teaching and in China

Adjusting myself to the Chinese way of life wasn’t my only challenge; I was learning to be a teacher at the same time. I did my best to learn from teaching methodology books, observe experienced educators, and seek advice on teachers’ blogs. Having no formal training worried me, but after a while I’d learned that all my colleagues were equally unqualified. The main differences between them and me?

- They were native speakers of English.

- They didn’t care about teaching at all.

- I understood English grammar better than they did.

- I understood students’ struggles with learning a foreign language.

Adapting to my life in a new country was parallel to my gaining confidence at work. I was eager to prove to myself that I can plan lessons combining fun activities with serious learning. After some time, my impostor syndrome faded and stopped feeling like a fraud. I even fell in love with teaching so strongly that I signed up for a CELTA training.

In many ways, moving to a new country is like starting a new job. At the beginning, everything is unfamiliar and you’re worried that you don’t belong there. Impostor syndrome creeps in and makes you doubt yourself. It’s tempting to give in and go back to the old environment, no matter if it’s your previous workplace or your home country.

So, how do you fight that feeling of not belonging?

- Remember the reasons why you decided to make your move. You wanted to improve your life in some way; maybe learn something, get a better salary, or start a new life in a more secure place. These reasons were important enough to prompt you to challenge yourself, and they most likely didn’t vanish all of a sudden.

- Remind yourself of your worth. Ever heard of any bosses who pay people for being unqualified? If they hired you, it means you’ve got the skills they need. Similarly, if you received a work visa to a new country, it means that this country needs your work. Or: if you got admitted to a demanding university program, then you certainly are smart enough to be there.

- Don’t focus on convincing others that you belong. Focus on convincing yourself. Impostor syndrome usually affects perfectionists and high achievers. In other words, if you were a fraud, you most likely wouldn’t feel like it.

- Reaffirm your qualifications. One good way to do that is to make a stock of your past achievements. Alternatively, you can establish a SMART goal that requires having skills you’re not confident with. Working toward achieving it can help you become assured of your worth.

Takeaway

All lives are complicated. Sooner or later, you may find yourself in a situation that makes you think: What am I doing here? I don’t belong here! I’m a fraud! Don’t let that inner critic discourage you from pursuing your goals! It’s likely that the people around you have also experienced impostor syndrome at some point. It doesn’t matter if you have it because you’re in a new country, an unknown city, or a new job—you can combat this negative feeling in various ways.

Have you ever felt like a fraud at work or abroad? I’d love to hear your experience!

Bibliography

- Jafarov S., Aliyev Y., (2024) What causes culture shock?, South Florida Journal of Development 5(7):e4106

- Statista, Youth unemployment rate in Poland from 1991 to 2024

- Hill A.P., Gotwals J.K., (2025) A meta-analysis of multidimensional perfectionism and impostor phenomenon, Journal of Research in Personality, Volume 118